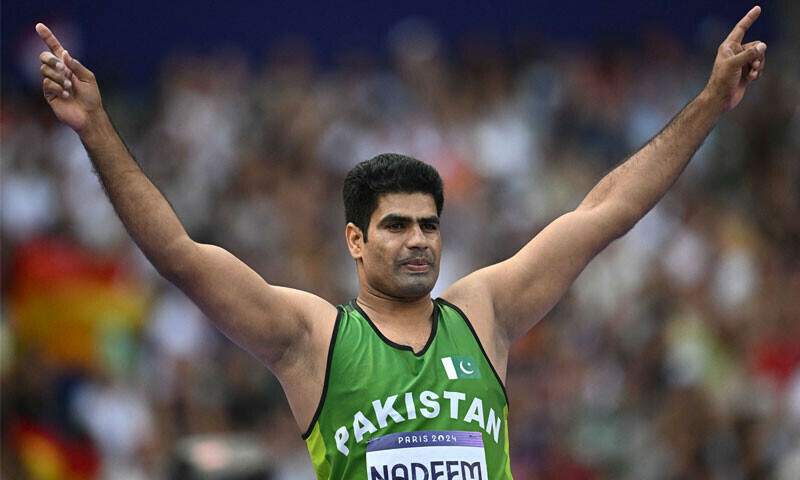

Arshad Nadeem cruised to the Olympic javelin final with a solid 86.59m throw in Tuesday’s qualifier round at Stade de France, keeping the nation’s hopes for an Olympic medal well and alive.His season best throw, the first and only of the qualifier, ranks him fourth heading into Thursday’s night finals.

Reigning Olympic and world champion India’s Neeraj Chopra led the field with a massive 89.34m throw, also a season best.Sandwiched between the two South Asians were Grenada’s Anderson Peters in third place (88.63m) and reigning European Champion Julian Weber in fourth with a 87.76m. All four athletes walked away from the qualifier round with a lone throw that saw them comfortably through to the final.

Kenya’s Rio 2016 silver medalist sealed a fifth place ranking in the final after an 85.97m throw in his third attempt, which was also a season best.Brazil’s Luiz Maurício da Silva was having a field day as he threw a personal best and broke the South American record with an 85.91m throw to land in sixth place.

Czech powerhouse Jakub Vadlejch ranks seventh in the field with an 85.63m lone throw, which stands a fair bit off from his season best 88.65m.Finland’s Toni Keranen got off to a flying start at his Olympic debut as his 85.27m throw doubled as a personal and season best to rank him eighth.

Yet another season best was achieved as Andrian Mardare of the Republic of Moldova threw an 84.13m to place him ninth heading into the final.

Arshad Nadeem is the best he can be. Yet, he has nothing. At least, nothing that makes him the best in the world. But he’s almost there, on the very cusp of it: a javelin throw away from making history and ending Pakistan’s three-decade long wait for an Olympic medal. It’s now about waiting and watching, and trusting the process. And praying. The only talisman he carries every competition is “puri mulkkeduaien.”

He will do so again at the Paris Olympics on Tuesday, when he steps into the Stade de France; an imposing venue that’s a far cry from the Punjab Stadium in Lahore where Arshad was training about a month ago. Arshad has been to the Games before; he finished fifth on his maiden Olympics appearance in Tokyo three years ago. He’s competed in Paris as well — but at the smaller Stade Sebastian Charlety only last month at the Diamond League meet where he finished fourth.

For all the venues across the globe he’s been to, he seems to have made peace with whatever decrepit facilities there are back home. The gym at the Punjab University is a throwback to the seventies. A cycling machine barely holds itself up in one corner, lumpy punching bags hang from another. The newest piece of equipment here is older than the 27-year-old himself, who has quietly begun stacking weights for his clean and jerk. The nakedness of a space that is supposed to be foundational in his quest for Olympic glory is startling.

Arshad changes from a light grey t-shirt to a dark grey one halfway through training, courtesy of the sweat dripping off him like a leaky faucet. “What will be left of him after all this sweat?” his coach Salman Butt quips before swinging back to Arshad squatting his own bodyweight, waiting for the “Up!” that comes from Salman, waving his arms like an orchestra conductor.